Population Day 1

Ramjee Lal Kumhar, right, and wife Mamta hold their toddler son Karan and infant daughter Kusum in their village in India’s northern state of Rajasthan. The couple are part of the largest generation in history -- 3 billion people under the age of 25. With so many entering or already in their reproductive years, the impact on the planet will be huge. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

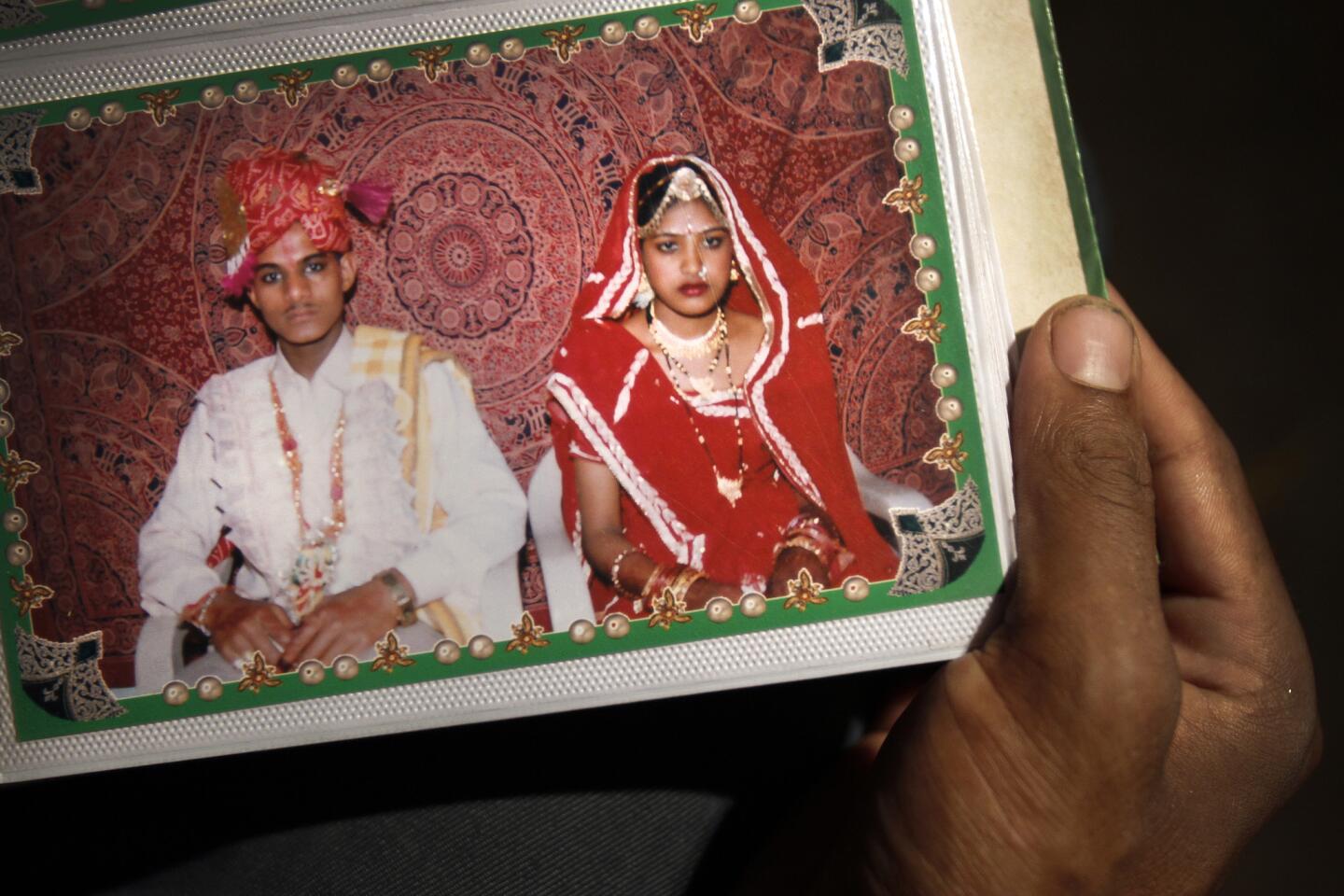

Ramjee and Mamta on their wedding day. The teenagers wed when she was 10 and he was 11, in a marriage arranged by relatives. Although Indian law restricts women younger than 18 from marrying, the tradition is so strong and enforcement is so lax that nearly half do so anyway, all but guaranteeing an early start to childbearing. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

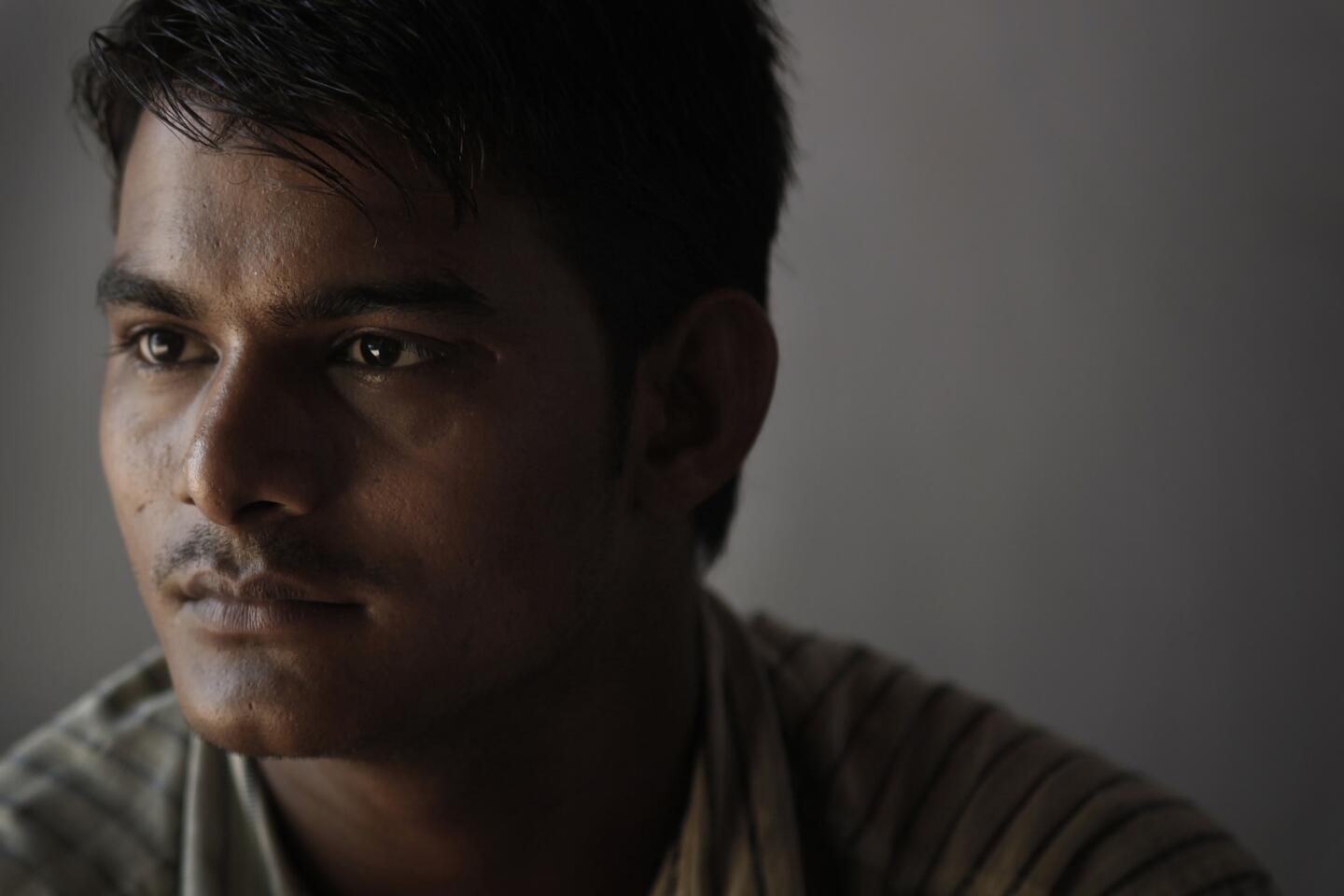

Ramjee had dreamed of finishing school and becoming a police officer, but after the birth of his first child, at age 13, he knew he had to put those ambitions aside. He made a decision, however - one that defied family tradition. He and Mamta would have just two children, in hopes of raising their economic standing. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Laxmi Devi Kumhar, mother of Ramjee, tends to his daughter, Kusum, as his son, Karan, looks on. Laxmi pleaded with Ramjee to have more children, but after his second child was born, he took his wife, Mamta, to a doctor and she had her tubes tied. “In today’s times, it is very expensive to have a third baby,” Ramjee said. “We cannot afford it.” (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Karan follows as his teenage father heads to work. Although India’s middle class is expanding, the population is growing most rapidly among the rural poor. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Mamta holds her daughter in the room she and her husband share with her extended family. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A crowded street in Varanasi, in India’s most populous state, Uttar Pradesh. At 200 million people, the state has more people than Brazil, the world’s fifth-most populous country. Uttar Pradesh is on track to double in population by midcentury. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Commuters fill the platform at the Chhatrapati Shivaji railway station in Mumbai. India’s leaders tout the country’s large, youthful population as a competitive advantage over China. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A commuter train speeds past the Dharavi slum in Mumbai, a megacity where half the residents live in squalor. Most of the world’s population growth in the next several decades will occur in places least able to handle it. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A train pulls into the station in Mumbai. The world’s population passed 7 billion in 2011, and it took just a dozen years to get from 6 billion to 7 billion. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A cabby waits for a fare in Mumbai. There are so many passengers that drivers routinely turn down those whose trips they consider too short. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

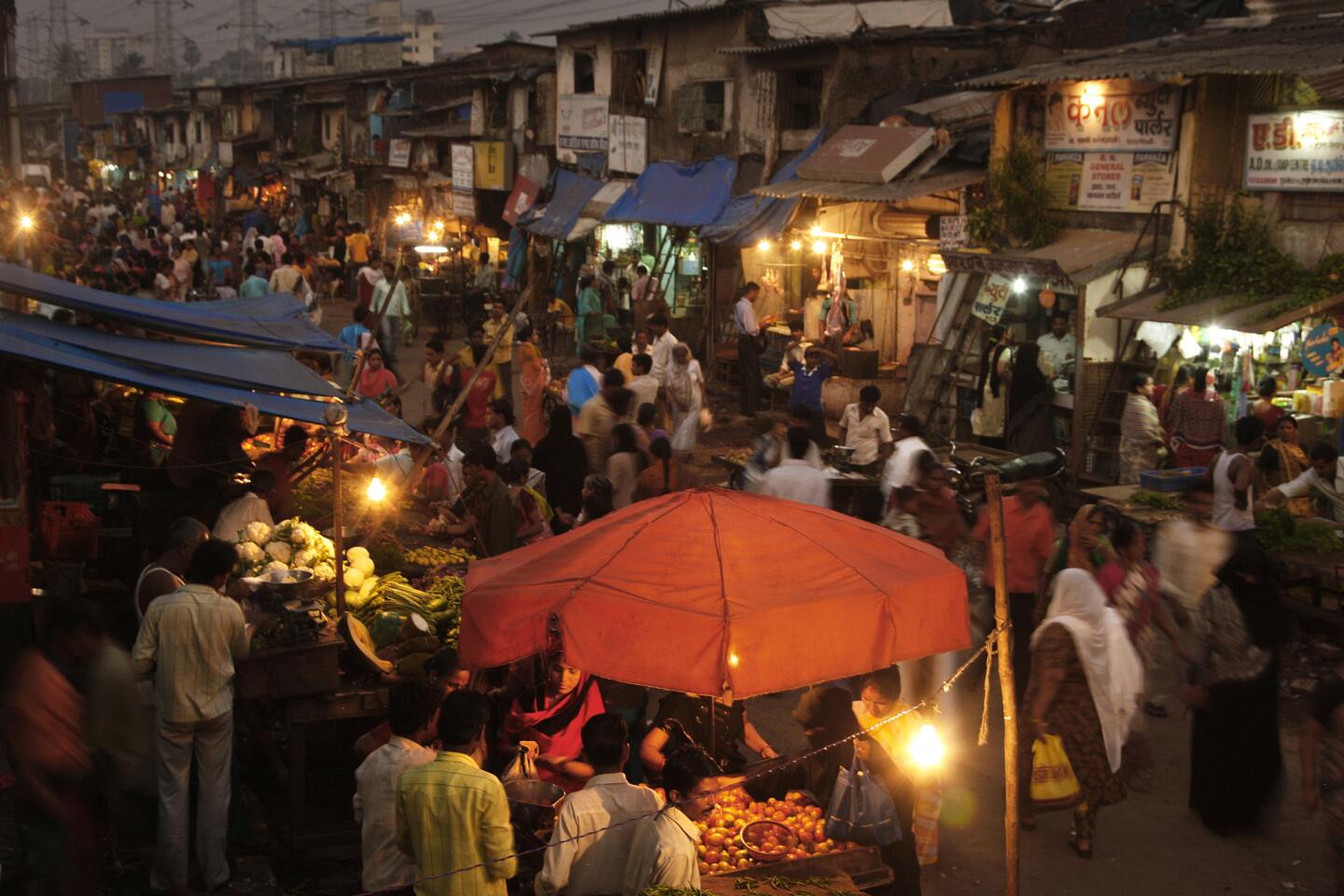

A marketplace in Mumbai, India’s most populous city. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A Mumbai produce vendor is surrounded by his wares. A revolution in farming techniques helped India overcome a food shortage in recent decades, but now those gains are on the verge of disappearing. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Zarina Haraiana with her three children in Hamariaka, an impoverished village in India’s northwestern state of Rajasthan. Many parents there want their daughters to wed as young as possible to ensure their virginity and reputations remain intact, and Haraiana was married a few months after her first menstrual cycle. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Gopal Pandey of the Sankat Mochan Foundation holds up a water sample from the Ganges River in Varanasi. The foundation works to increase awareness of the poor quality of the water, which carries high levels of fecal bacteria. The river, considered sacred by Hindus, is used by millions of people for bathing, worship and as a sewage outfall. Health problems have flourished along with the contaminants. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Sunrise draws many observant Hindus to the Ganges in Varanasi. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

More than 60 members of one extended family live in this house in Ladana, in Rajasthan state, which was originally built by three brothers soon after they married. The three-story house has expanded to accommodate three generations of large families. It now has eight communal bedrooms and six kitchens, including this cluster of cooking areas on a rooftop terrace. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A farmer tends a pile of burning chaff just after the rice harvest in Punjab state. Forty years ago, the state tripled its grain production with the introduction of chemical fertilizers and improved irrigation, the so-called Green Revolution. Now wells are running dry and soils are spent or contaminated. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Pal Singh, a migrant worker who has been farming since he was 10, emerges from the haze in a field where rice chaff was being burned. Authorities have tried to crack down on the practice, which robs the soil of nutrients from decomposed plant material. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A farmworker threshes rice over a barrel. Punjab state’s grain production is crucial to feeding the rest of India. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The output from farmers in Punjab has earned the northwestern state its title of India’s breadbasket. Yet agricultural production isn’t keeping pace with population growth. Barring a breakthrough of some kind, the country will again have to rely on handouts or imports to feed its multitudes. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

On the outskirts of Lucknow, the capital of Uttar Pradesh state, a young girl, left, waits to receive a midday meal provided by CARE India. Despite India’s economic boom, nearly half the nation’s children are underweight and about one-third of its population lives in extreme poverty. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Preschoolers sit with empty bowls as they wait for a porridge of lentils and rice provided by CARE India. “We are doing the best we can,” said Anup Murari Rajan, an officer with CARE India, which provides free meals at 32,000 community centers in Uttar Pradesh state. “These slums are increasing day by day.” (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Children listen as they await a supplemental midday meal at a community center on the outskirts of Lucknow. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Madhuri Devi, 32, rests after giving birth in Lucknow. Surveys have found that nearly a quarter of women of childbearing age in Uttar Pradesh state do not use modern birth control methods even though they want to avoid pregnancy. Many are in rural areas and cannot travel to health centers or cannot afford the contraceptives. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Priyanka Panwar walks downstairs with her daughter in Muzaffarnagar, 70 miles north of New Delhi. Married at 14 and with two children by age 19, she joined about 100 other women one day in lining up at a local clinic to receive a pregnancy test, exam, consultation and IUD -- all for about $3.30. India’s government has taken little action to provide broad access to family planning, and such services are mainly offered by nonprofit groups. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Indians in a village without electricity in Uttar Pradesh state turn out for the novel experience of watching a Bollywood movie projected on the side of a building. The film -- presented by the nonprofit group World Health Partners to promote rural health clinics -- was occasionally interrupted by commercials on family planning. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

So-called rag pickers search for food and recyclable materials in New Delhi’s 70-acre Ghazipur landfill, where a vile stench permeates the air. The amount of trash generated in the city is expected to double in the next few years. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

The Dharavi slum in Mumbai. About 1 in 8 people in the world lives in a slum, and U.N. officials say that if current rates of poverty and urban migration continue, the ratio will be 1 in 3 by midcentury. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Residents of a Mumbai slum live in close quarters. Some of the homes have electricity, but few have running water. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A boy in the Dharavi slum is dressed for school. Mumbai’s huge shantytown is a city within a city, with schools and businesses inside its boundaries. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A man works late into the evening in a warehouse in Mumbai, creating soles for shoes that will be exported to other countries. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A girl is led through mounds of trash in an area that many call home in Mumbai. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Boys play cricket in the Dharavi slum. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A woman begs for coins at the Chhatrapati Shivaji railway station in Mumbai. The World Bank has reported that 32.7% of Indians live on less than $1.25 a day (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Many of Mumbai’s residents are homeless and sleep where they can. The hordes who leave their rural homes in search of a better life in the city often find little opportunity in their new surroundings. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A boy takes advantage of a broken water pipe on the outskirts of the Dharavi slum. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

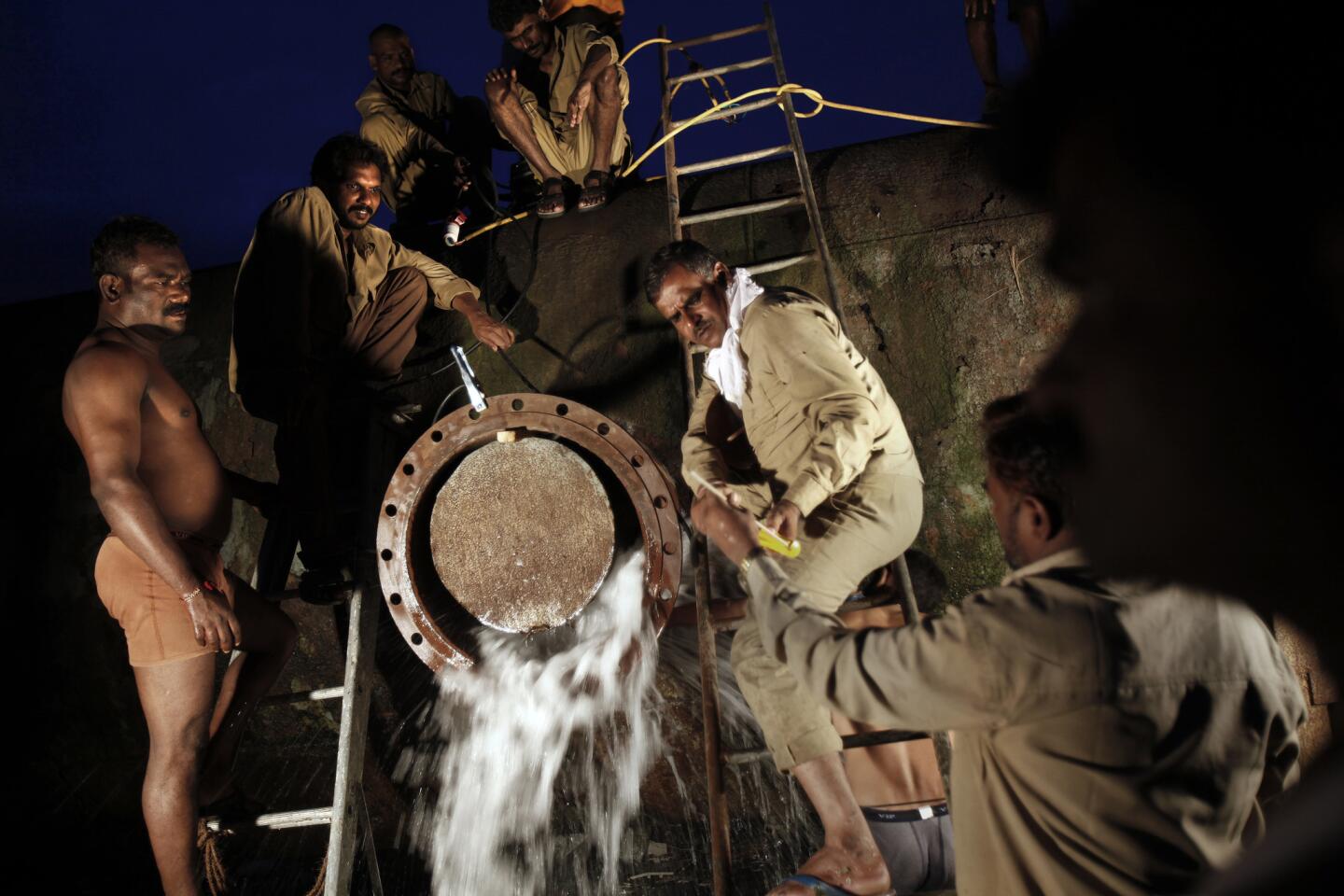

Men work in darkness to repair the water line that runs through the slum, where water is often in short supply. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Sarabjit Kaur poses for a picture after her wedding in the tiny village of Galib Khurd, in Punjab state. The lavish wedding ceremonies for her and her four sisters cost her father, a farmer, a small fortune. The tradition is adding to the cycle of debt for already-struggling farmers. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

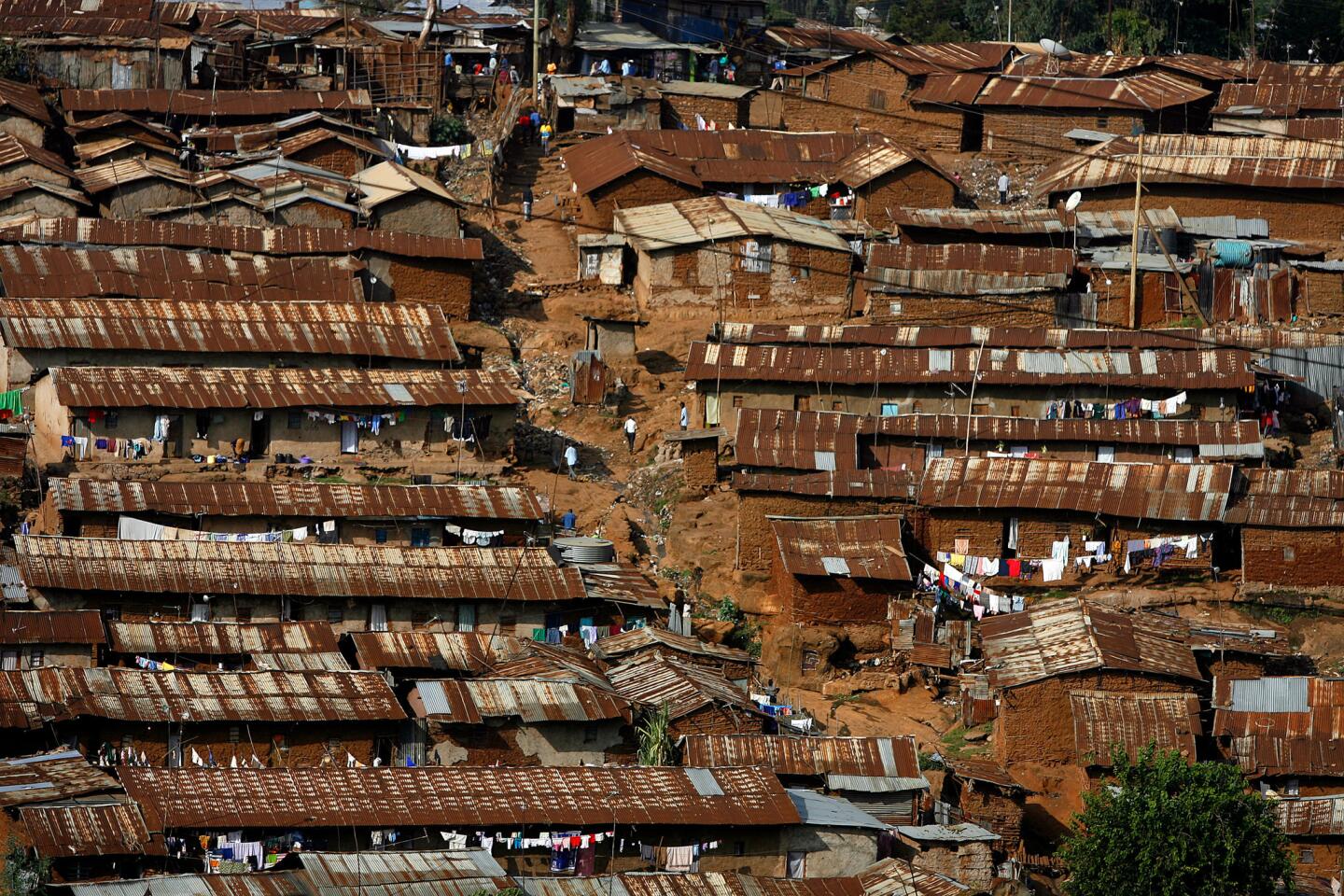

The Kibera slum in Nairobi is Kenya’s largest. Hundreds of thousands of people, mostly migrants from rural areas, are packed into 500 acres that a century ago were grazing land and acacia forest. Slums are spreading around Africa’s major cities as the continent’s population soars. The United Nations projects that by midcentury, Africa’s population will have doubled to 2 billion, and most of those people are expected to be living in urban slums. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

A woman is in labor at a health clinic in the Nairobi slum of Korogocho. Kenya’s family planning program was once held up as a model for Africa, but political turbulence in the nation and cuts in U.S. funding interrupted supplies of contraceptives. The population is climbing rapidly. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Francisca Kanyari heads home with food for her family in a village near Nanyuki, Kenya. She receives a shot of the hormonal contraceptive Depo-Provera every three months -- secretly, because her husband wants her to have more children. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Francisca Kanyari had two children by age 20, and her husband had six others with another wife, in a country where polygamy is legal. Kanyari believed she and her two boys would be better off if she stopped having children. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

A mobile clinic run by Community Health Africa Trust makes its way via camel caravan to another remote settlement in northern Kenya. Covert contraception programs have emerged throughout Africa, where women often face opposition to birth control from their husbands and in-laws. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Women line up at a mobile clinic in Samburu, Kenya, where the services include contraception and family planning education. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

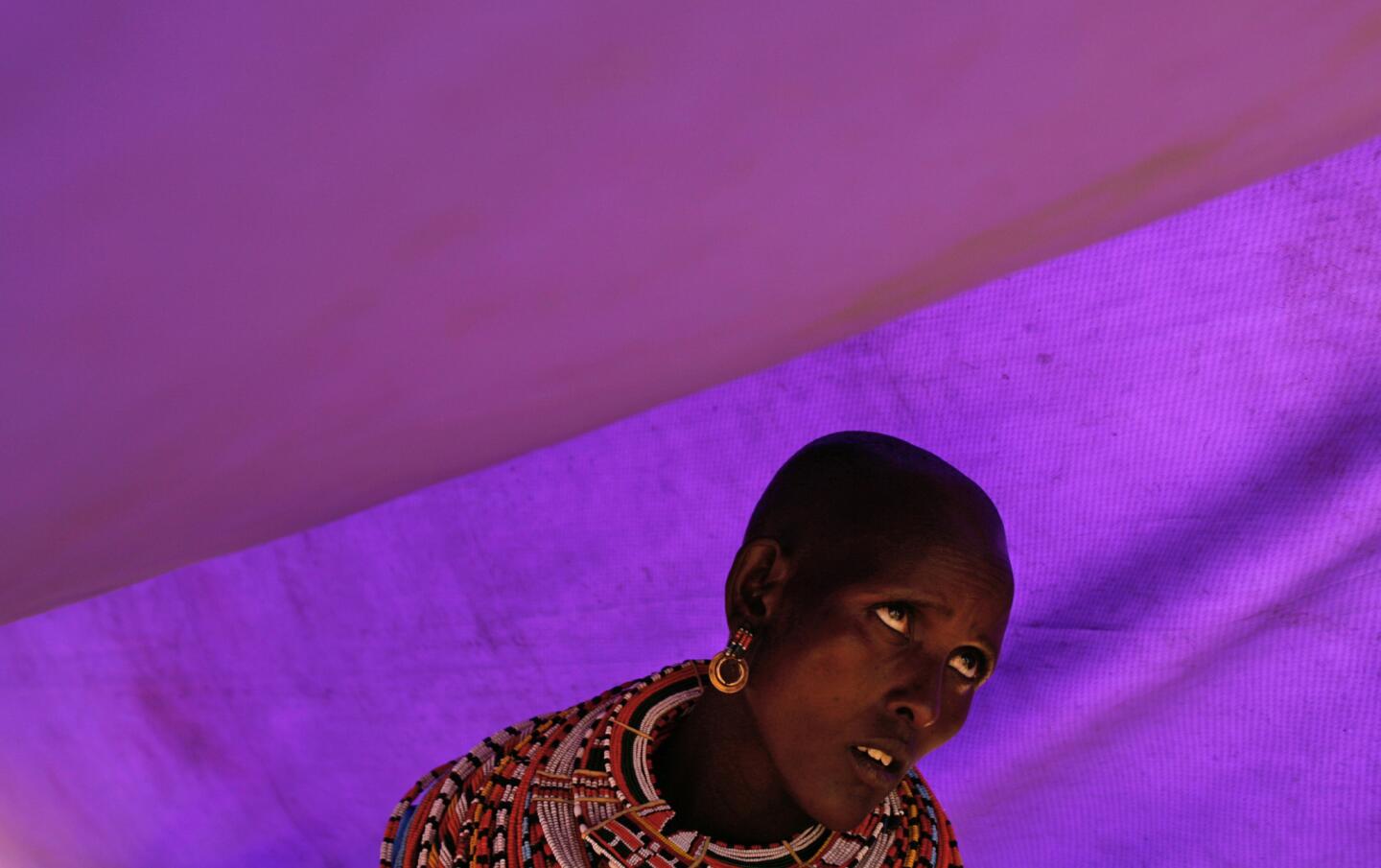

A Samburu woman is given an AIDS test at the clinic, where the staff’s primary goal is to provide basic medical services and contraception. Some women use the basic services as their excuse at home for visiting the clinics to receive family planning help. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Women sit in the shade of a tree as a clinic worker discusses family planning. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

The mobile clinics travel to remote areas of Kenya in an effort to reduce child mortality and educate women on the health benefits of smaller families. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Members of the mobile clinic load supplies onto one of the camels used in the months-long treks. (Rick Loomis / Los Angeles Times)