Explore the ‘Hot Tub of Despair,’ an underwater lake that kills almost everything inside

- Share via

They call it the “Hot Tub of Despair.”

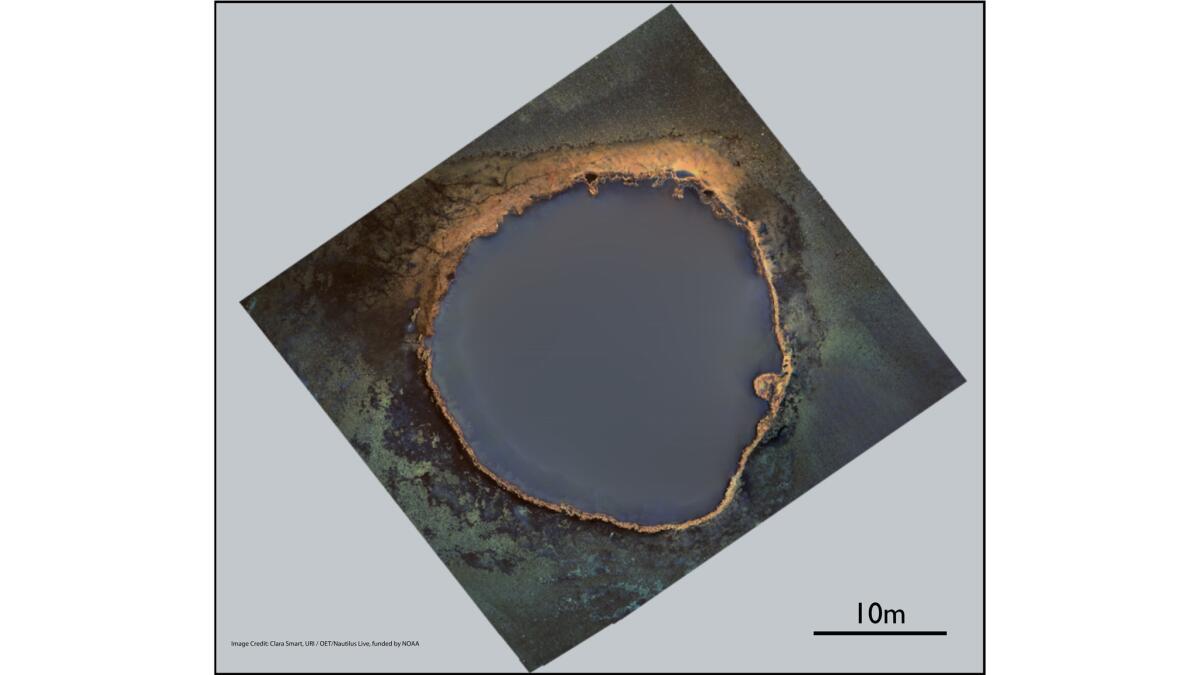

The underwater lake, discovered 3,300 feet below the surface of the Gulf of Mexico, is a pit of super-salty water and dissolved methane that kills any critter unlucky enough to fall inside.

The discovery was made last year by a San Pedro-based research vessel, the E/V Nautilus.

In the video, scientists excitedly navigate a remotely operated vehicle, the Hercules, above the circular pool. They point out the “pickled crabs” that succumbed to the elements.

“These larger organisms really don’t like to be in this fluid — or maybe they just come here to die,” Scott Wankel, a marine chemist, says on the video.

Such brine pools offers scientists a glimpse into the odd world of underwater biology and geology. Hercules’ observations from the pool were described in a recent report in the journal Oceanography.

“We’ve known about [brine pools] for 30 years, [but] this one was pretty spectacular when it was found,” said Erik Cordes, a Temple University biologist and coauthor of the Oceanography study. “It’s one of the coolest ones I’ve seen.”

Though Cordes wasn’t on the cruise that observed the “Hot Tub of Despair,” he’s explored similar underwater lakes and rivers in the Gulf of Mexico, all of which boggle the mind.

In 2014, Cordes piloted the Human Occupied Vehicle known as Alvin to an underwater river, with brine so dense he could land the sub on top of it.

“It’s very disorienting to go down there and ‘land’ on a lake or a pool on the bottom of the ocean and try and recognize that you’re in the deep sea,” he said. “This isn’t just a pond in a backyard.”

See the most-read stories in Science this hour »

These underwater lakes formed over millions of years as a much shallower Gulf of Mexico evaporated and left behind massive beds of salt. Over time, the salt layers became submerged and buried. Under the weight of these sediments, the salt layers shift and crack the shale above, allowing oil, gas and brine to escape.

The result is a super-salty brine so dense it doesn’t easily mix with the seawater around it. The brine then pools into underwater lakes, rivers and “spectacular” waterfalls, the scientists wrote.

The body of water, which they also refer to as the “Hot Tub Brine Machine,” is a crater-like pool that rises 12 feet above the ocean floor, surrounded by bright red and white mineral deposits.

“You don’t expect to see [these bright colors] in the muddy background of the deep sea,” Cordes said. “It’s very weird. I think that’s what’s captured people’s imaginations. It’s such a bizarre kind of habitat.”

Mussels living on the edge of the lake help keep its outer walls intact.

In the video, the cloudy brine can be seen cascading over the side of the lake.

The mussels survive in the deep ocean thanks to a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that live on their gills. These bacteria use dissolved gases — such as methane and hydrogen sulfide seeping from the ocean floor — to make energy for the shellfish. Fields of tube worms survive alongside similar bacteria.

While mussels thrive along the pool’s edge, the brine itself is toxic to most sea creatures. The fluid contains almost no oxygen and plenty of toxic chemicals, such as hydrogen sulfide and methane, that almost instantly kill fish and other sea life that come into contact with it. The brine, four times saltier than regular ocean water, preserves the unfortunate critters.

“It could be decades that the crabs have been there upside down,” Cordes said.

To measure the pool’s salinity, temperature and depth, the Hercules lowered a sensor down into the pool. From the lake’s surface to a depth of about 10 feet, the brine was a relatively warm 46 degrees Fahrenheit. At that depth, the Gulf of Mexico is about 40 degrees.

As the sensor sank deeper, the temperature rose further, to 66 degrees. The probe plunged more than 62 feet into the brine pool but never reached the bottom.

“Since the source of the brine and hydrocarbons is basically a crack in the Earth, it is tough to find the bottom,” Cordes said. “It could be a few kilometers down under the seafloor.”

Follow me on Twitter seangreene89 and “like” Los Angeles Times Science on Facebook.

MORE SCIENCE NEWS

Chimpanzees need friends too — their stress levels show it

Accepting more Facebook friend requests is linked to lower mortality, study says

UPDATES:

Nov. 4, 9:55 p.m.: This story has been updated with quotes and information from Temple University biologist Erik Cordes.

This story was originally published on Nov. 2 at 9:50 a.m.